Cut fast (or slowly) between these: larger than life images of teen idols in bright cyberpunk neon, William Gibson’s scenes of seedy capsule hotels, and various slightly suspect activities revolving around some archetypal 7-eleven. Haruki Murakami’s comfortingly familiar (if stale) fog of noodle bar vapors, a series of lovingly personal metro stations, the absentminded faces of cram school teachers, and the precisely measured subway routines of a plausible massage therapist.1 Then, manga-inspired images from a decades old book of beautiful drawings: Brian Boigon’s Speedreading Tokyo; a pan across stacks of maneki-neko cats frenziedly waving their paws captured by the cat-loving director Chris Marker; the deceivingly simple, translucent axons of Made in Tokyo and Pet Architectures, the yellowing images of the Osaka Expo, Project Japan’s intimate slice of Metabolist dreams, aggregating across the Tokyo bay…these were other people’s sensations, interventions in the realm of the city’s image that have fully framed my own experiences.2 I recognize them as I walk around, the way a lover might “recognize” the shape of their loved one in the gestures of strangers. Tokyo is not alone in this. All cities are framed for us by experiences of others, rendered and transmitted in various forms of aesthetic products. That is how we know intimately that culture is transformative; and it is transformative even when its influence is harder to discern—subtler, less intentional.

For our Slowgramming Tokyo workshop, with many of our participants freshly arriving to the city and a few key ones with intimate knowledge of it, we responded to the contemporary phenomena of private image dissemination (at unprecedented speed) across social media. Instagram seemed like a pleasantly stylized encapsulation of this phenomenon, its square images an approximation of the indexical nature and immediacy of Polaroids, but now inhabiting that “consensual hallucination” that Gibson dubbed “cyberspace” in the early 1980s.3 Cyberspace is now delivered with less punk and onto the screens of our pocket-sized devices. We all now carry it with us. These Instagram images, too are a dimension of contemporary culture. Though hardly authored the way a Murakami novel might be, the quick snaps and selfies are now pervasive. The logic of their dissemination and the habits of use we have developed in response are both equally symptoms of the technological reality that has begun rewriting our own. Architecture, and its valuation are subject to this unprecedented speed of recording and retrieval. Today the contemporary city, like contemporary architecture, travels far and instantly, as a collection of 2D, 1080 x 1080px images (recently adjusted for retina display capabilities), often snapshots taken for one’s personal scrapbook and casually shared with the public, then “hearted” and “liked,” with their mere exposure being the index of their value. Images of food intermingle with architectural details, saccharin sunsets, and family birthdays—the frameworks that give each of these their value is flattened and made uniformly more personal. We considered the view of Tokyo assembled in such a myriad of images, in order to get a sense of what might be most relevant and enchanting to a statistical multitude. What were the sites that signify Tokyo to a networked global audience, both real and virtual? And if the Nagakin capsule tower is not one of them, how do we prop it up into general view and greater understanding—beyond the love it inspires among its architectural devotees?

The Slowgramming Tokyo workshop rested on two hypothesis. One, that our initial engagement with the instagram portrait of Tokyo would lead us first to a form of “reflective nostalgia” for the depth and the complexity of understanding that has been removed by definition—since Instagram indeed promises and delivers an instant record free of time and baggage—and through that nostalgia to criticality about the loss of historical, social, financial and human narratives that go into the production and practice of cities, and with those, also criticality about Tokyo’s contemporary developments.4 The second hypothesis was that the medium of exhibition was the most effective way for the participants of the workshop to reverse into, or at least cross-pollinate, insta- and slow-, reflexive and reflective, superficial with various forms of depth. Working in the exhibition medium also insured that the outcome of our collective research was, by definition, a discursive product with the capacity to challenge the cycles of recording and retrieving. We hoped it would do so in part by capitalizing on the precise alignment between those cycles and the features of contemporary attention spans.

Architectural exhibitions have been important sites of testing, disseminating, and consensus-building in the field. Just as much as the narrative of architectural modernism is hard to imagine without MoMA’s 1932 International Style exhibition, the early definitions of architectural postmodernism were deeply indebted to the first Venice Biennale of Architecture in 1980, titled The Presence of the Past. Similarly, the cultural exchange and competition during the Cold War played out in part on the grounds of international expositions and trade fairs, the early 1990s digital turn is unimaginable without its mesmerizing 1:1 installations, and more recently, architectural green-washing got its most in-depth critical review in Behind the Green Door at the 2014 Oslo Architecture Triennale. The contemporary view of architectural exhibitions’ potential for disciplinary contribution varies among curators, who see them as platforms for atmospherics (Henry Urbach), for contextualization (Mirko Zardini), for activism (Barry Bergdoll) and for storytelling (Jean-Louis Cohen).5 Depending on the cache of the institution, or the curator procuring them, exhibitions tend to also confer value on things (think MoMA again, or the contemporary mushrooming of biennales), but I believe their most valuable function is to provide a highly focused and selective mirror, which might indeed contextualize, tell stories, or transmit an atmosphere in order to move us toward positionality and even action. In the Slowgramming Tokyo workshop we imagined the architectural exhibitions as a form of making public of both architectural research and criticism; and thus an important mode of producing reflections on the discipline, that eventually lead to the strategic preparation for seeing and thinking an alternative—a slower, messier, more loving, and more critical alternative.

Ana Miljački

- The first set of these is loosely referencing several of William Gibson’s novels, but the key one to consider, the cult one to consider is William Gibson, Neuromancer (original publication London: Victor Gollancz, 1984). The Murakami list is most closely related to his relatively recent 1Q84 (first English translation New York: Knopf, 2011).↩

- See Brian Boigon, Speed Reading Tokyo (Tokyo: P3 Alternative Museum, 1994), Chris Marker (directed) Sans Soleil (France 1983); Junzo Kuroda, Momoyo Kaijima, Yoshiharu Tsukamoto, Made in Tokyo: Guide Book (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing Co, 2001); Atelier Bow-Wow, Pet Architecture: Guide Book (Tokyo: World Photo Press, 2002)↩

- Gibson, Neuromancer.↩

- Late Svetlana Boym distinguishes between two types of nostalgia, restorative, the stuff that nationalism is often made of a kind of return home, and reflective, which recognizes the stuff of the past is gone and thus has the capacity to frame a critical view of the past and of the present. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2002).↩

- Some of these positions were collected in Log 20, Curating Architecture (Fall 2010).↩

Students: Guillaume Antoine, Jolliet Charly, Stedndahl Linn, Li Linxi, Shino Hagio, Volodymyr Dereznichenko.

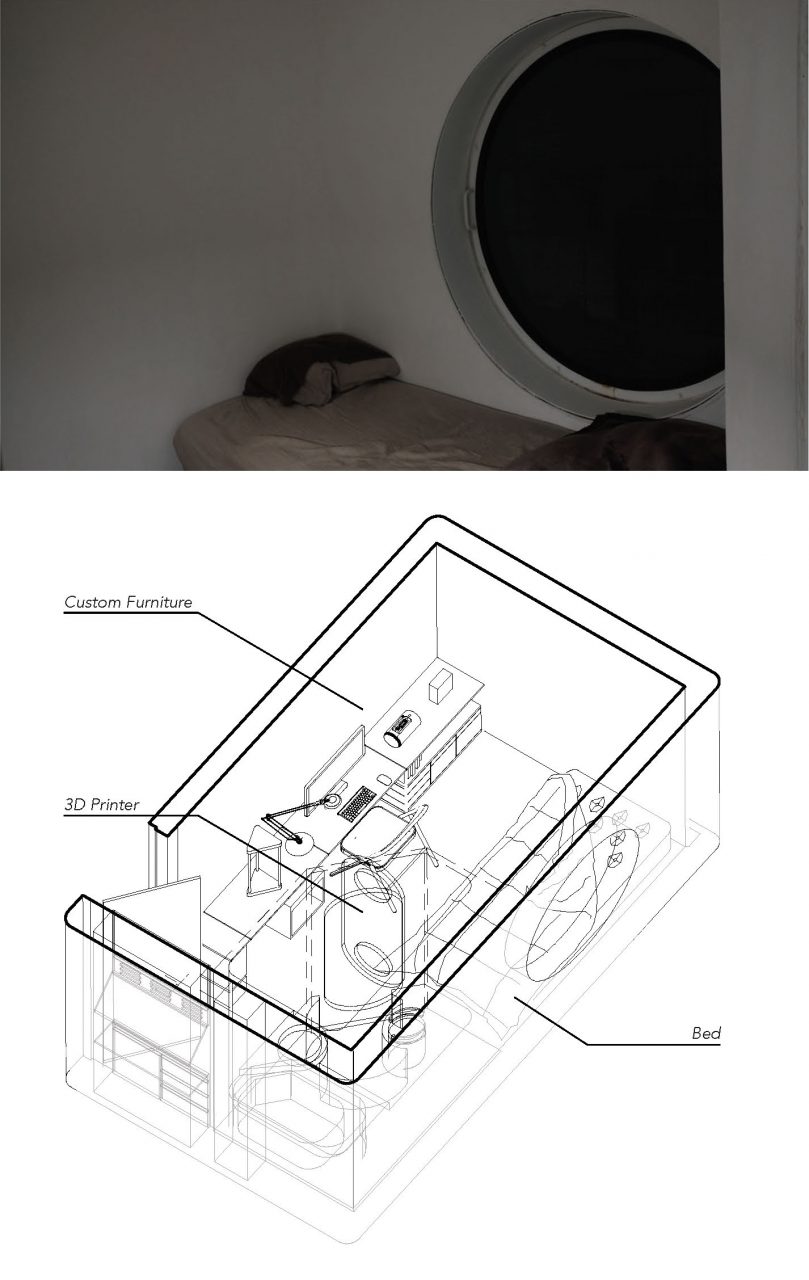

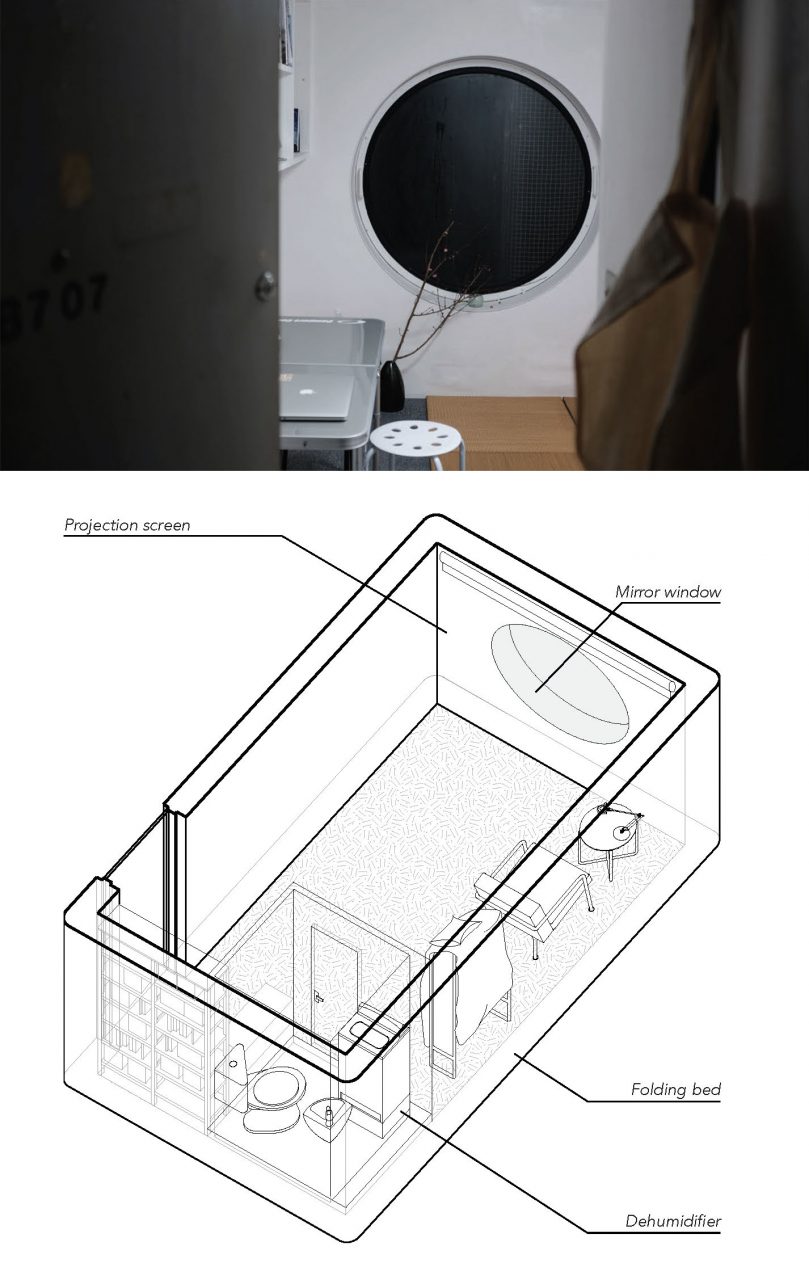

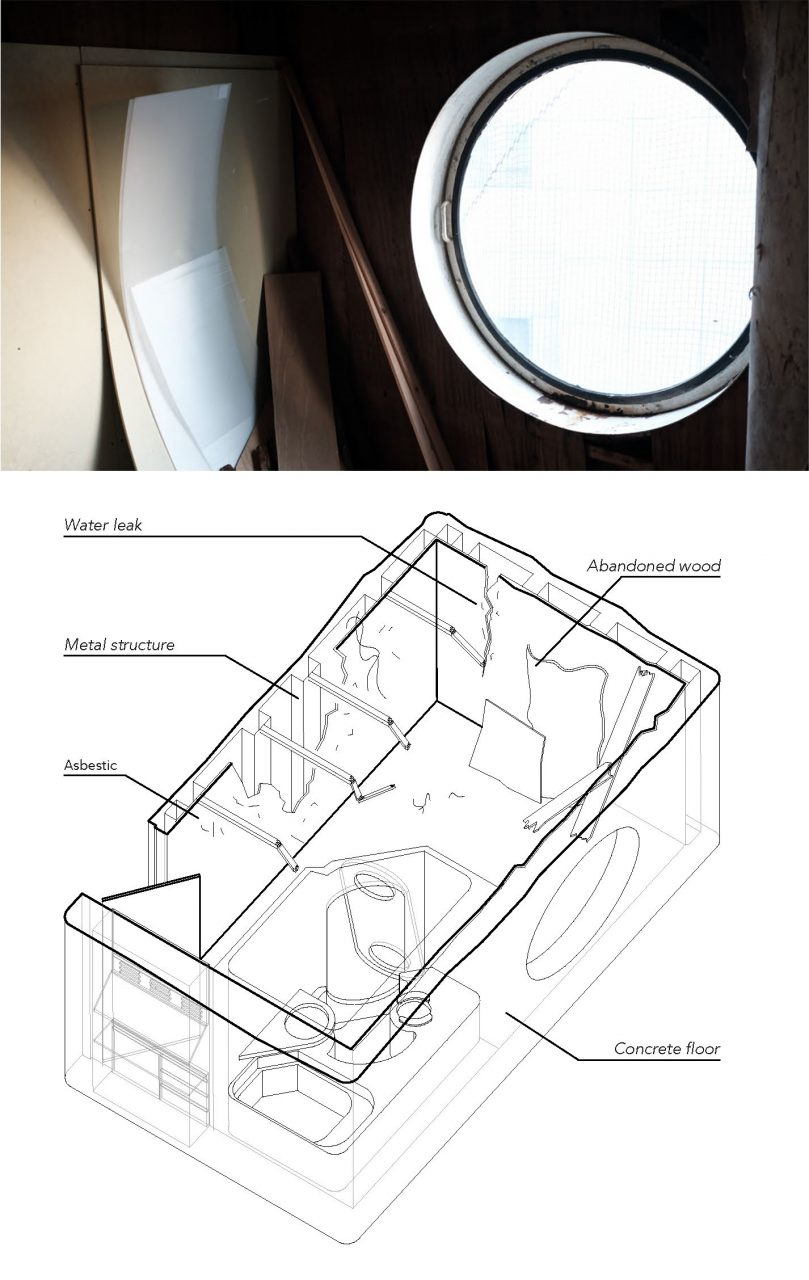

Dream of Individuality documents a series of capsules from Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower in their current state.

Capsules for people who miss last trains

The first capsule hotel was the Capsule Inn Osaka, which was build in 1979. It was originaly sauna company. At that time Japan was in good economic situation, and saunas were used by businessmen who worked until late night and missed last train. But the night before the Japanese National Railways strike, the napping rooms were especially overcrowded, and some people slept in the corridors. Looking for a way to solve this problem, the manager remembered the Capsule House in Expo ’70. He reached out to Kisho Kurokawa, who capsule-style hotel which can accomodate double the people as a standard hotel. The Capsule House from Expo ’70 became the Capsule Hotel.

Capsule lovers prevent the demolition

The construction of the Capsule Hotel was completed in 1972, and 43 years after its opening, it continues to age. In 2007 a demolition plan was set up, but which has been stalled because of the financial crisis. The building has not yet been demolished.

The building is a condominium, and many capsules have complicated ownership issues, such as being in the middle of an inheritance process. Mr. Maeda works as a representative of the Ceramic Capsule Tower Building Preservation and Reconstruction Project. “He hopes to be able to preserve the building with a large-scale repair. There are many people who love this building and enjoy living there, the media are increasingly talking about it, and he is often flooded with requests from overseas visitors.”

As part of the preservation movement, he gathered funds through a crowdfunding campaign and published a series of photographs of the building. The building has become such a popular property, that it is expected to be sold as soon as it is put in the market.

Students: Mohammsd Ali Eimer, Stefano Andreatta, Hans Henrik, Huang Ke, Siena Hirao.

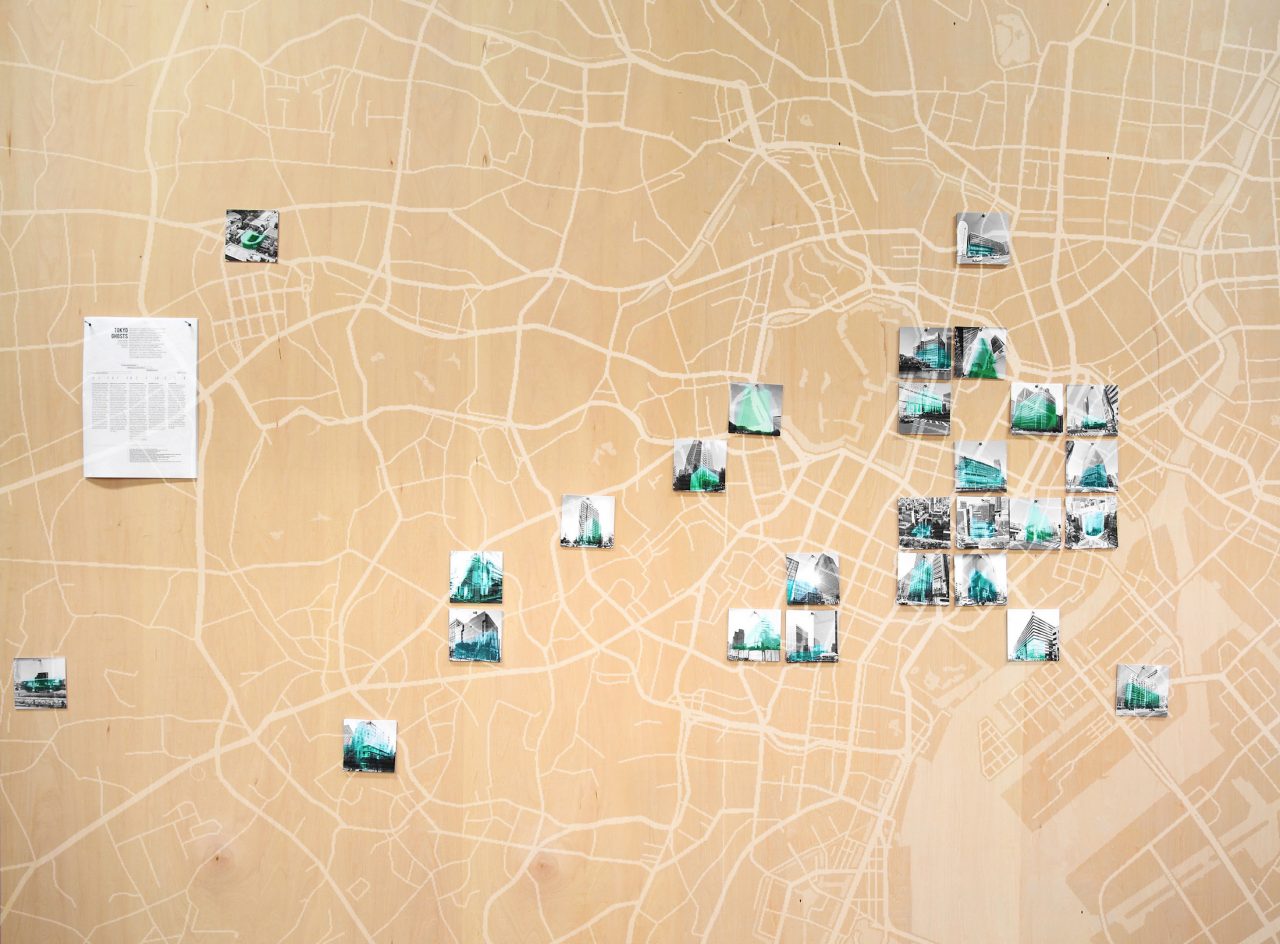

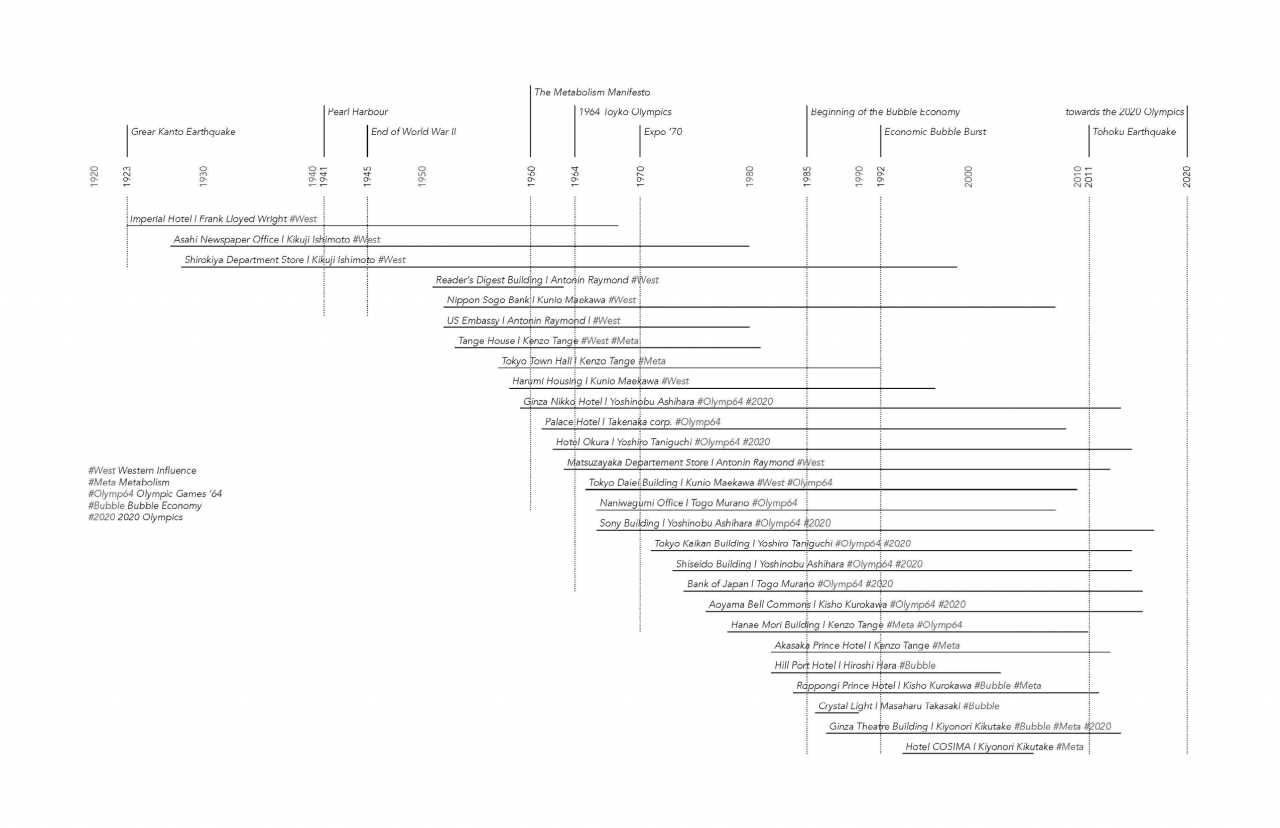

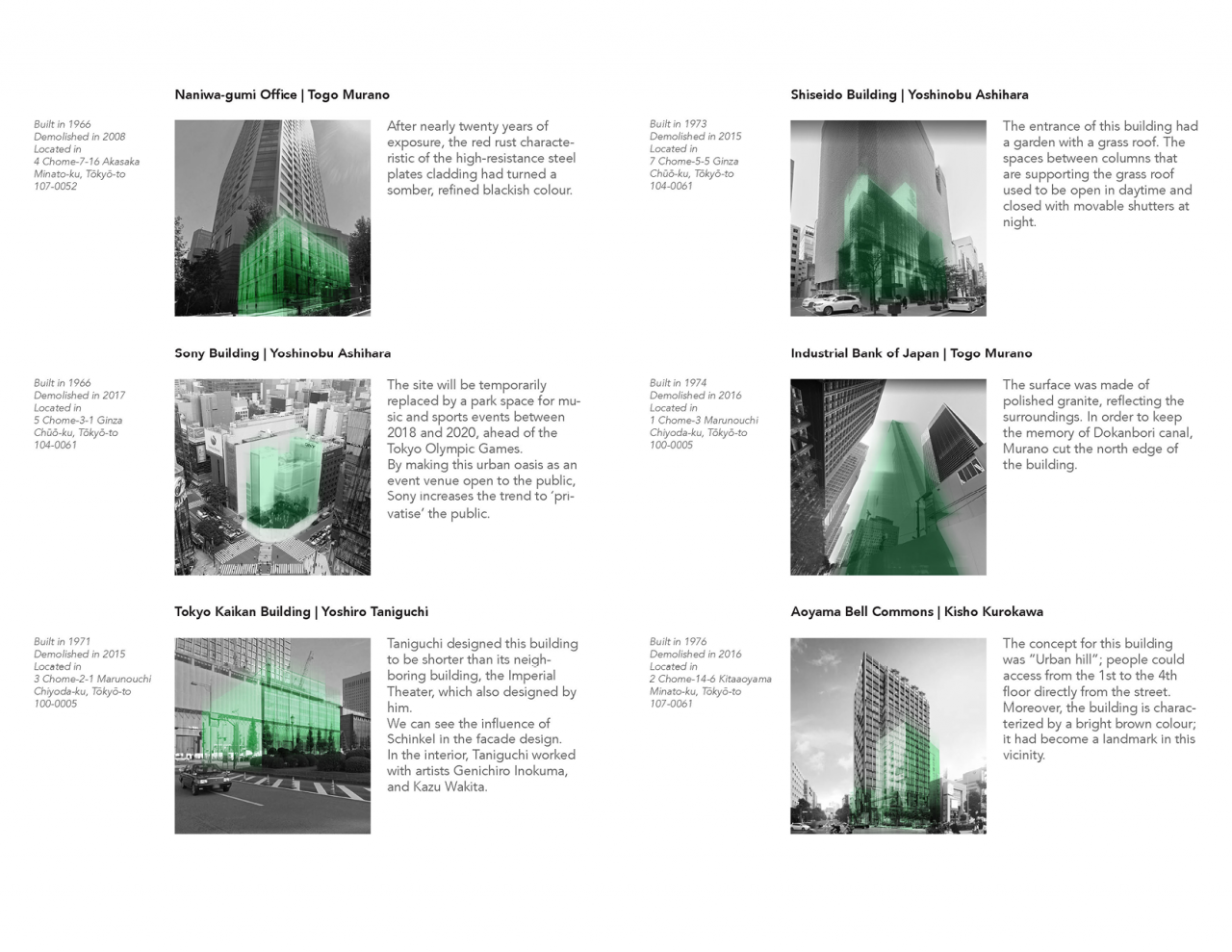

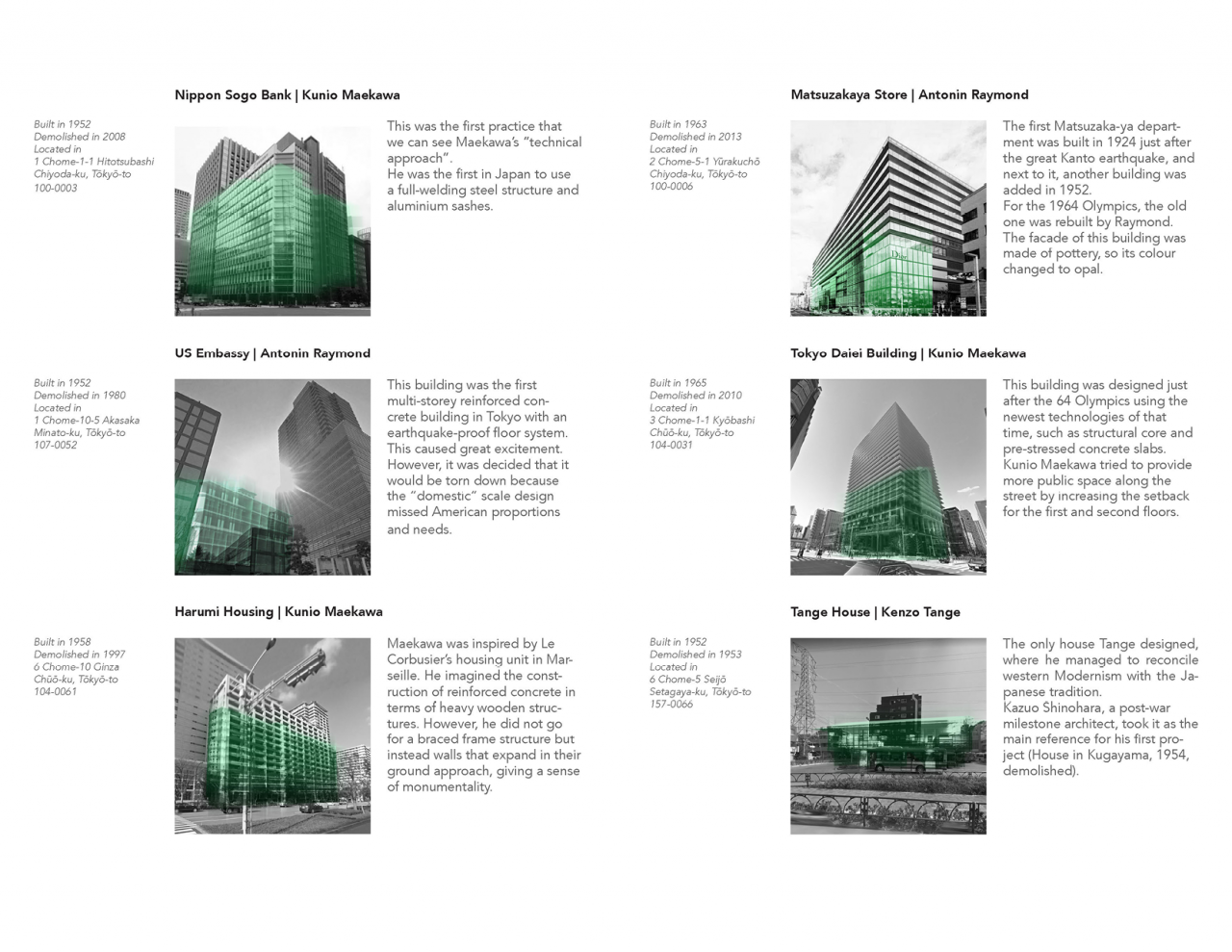

Tokyo Ghosts documents a series of ghost buildings in Tokyo–buildings that have disappeared or are planned to appear.

Western Influence

In 1853 Japan was opened to the West. In the following years ano in particular during the Meiji Restoration beginning in 1868, Japan underwent a rapid program of modernization. Western models were applied to Japanese cities along with the obsession to emulate the West in terms of urban planning and architectural design. But also Western architects drew attention to Japan. Among those architects were the American Frank Lloyd Wright, the Czech Antonin Raymond and the German Bruno Taut, for example. Some of them even had the chance to build in Japan. On the other hand, Japanese architects like Kunio Maekawa, who worked at Le Corbusier’s office, or Kikuji lshimoto, who studied at the Bauhaus in Weimar, became familiar with the ideas of modern architecture and introduced them to Japan.

Metabolism

Kenzo Tange was one of the most important architects in the 20th century, combining traditional Japanese styles with modernism. Furthermore, he is considered as the father figure of the Metabolists, the last movement that changed architecture.

Organized by Tange, a group of young architects including Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, and Fumihiko Maki presented their Metabolism manifesto at the Tokyo World Design Conference in 1960. Apart from a series of four essays and other designs, the manifesto included Kikutake’s floating city and Kurokawa’s well-known capsule tower.”

The metabolists tried to combine ideas of megastructural architecture with those of organic biological growth. Recognizing that certain elements in the built environment would wear out or become obsolete, they proclaimed building parts have to be interchangeable. Although there was a contradiction between the theory and their realized architectural megastructures, which turned out to be rather monumental and inflexible, the spirit has survived.

Olympic Games 1964 and 2020

Tokyo was chosen to host the 1964 Olympic Games. The event was significant for Japan as it returned to the global stage as a peaceful, economically confident nation. Besides rapid constructions of major infrastructure projects, Japan’s society embraced internationalization ahead of the 1964 Olympics in anticipation of foreign tourists expected to visit Japan for the event. The Japanese government faced with the urgent challenge of completing a massive construction effort in Tokyo to host an estimated 30,000 international visitors. In the aftermath of the 1964 Olympics, Japanese architects were beginning to imagine a new, stronger and more confident city. This was a massive undertaking, “with some estimates suggesting Tokyo spent the equivalent of its national budget on a major building program that transformed the city’s image.”

Towards the Olympic Games in 2020, the city seems determined to wipe out some traces of its past in order to show a new, strong image of Tokyo, as well as a confident and open minded image of Japan. After a period of economic stagnation lasting for almost 20, years as well as facing a rapidly changing population, the 2020 Olympics are expected to have a positive impact not only economically but also psychologically, similar to 1964. Owing to this the city is undergoing massive redevelopments and reconstructions. Many buildings, such as hotels, banks, offices and commercial buildings will be rebuild or reprogrammed by structures more appropriate to the social, economic and technological demands of the future. The ghost towards the 2020 Olympics already includes a vast number of buildings.

Bubble Economy

During the economic bubble, real estate and stock market prices were greatly inflated. Consequently, the economic bubble forced the process of demolition at a delirious rate. According to a 1993 statistic, “more than 30% of all [Tokyo’s] structures… have been built since 1985.” To make deals more attractive to buyers, in some cases buildings were even removed before the land was traded since the value of a building in many cases is only 10% of the property’s value. Ito’s U House was demolished due to those reasons. On another level, Japanese architects began to realize that their buildings are not long lasting under such conditions. Instead of striving for monumental permanence, contemporary design has turned into an architecture characterized by ephemerality and Tokyo has become an urban laboratory for architectural experimentation.

Students: Ji Yuxin, Shimura Selma, Tam Kinlaam, Kai Kasibuchi, Gondo Hiroyuki.

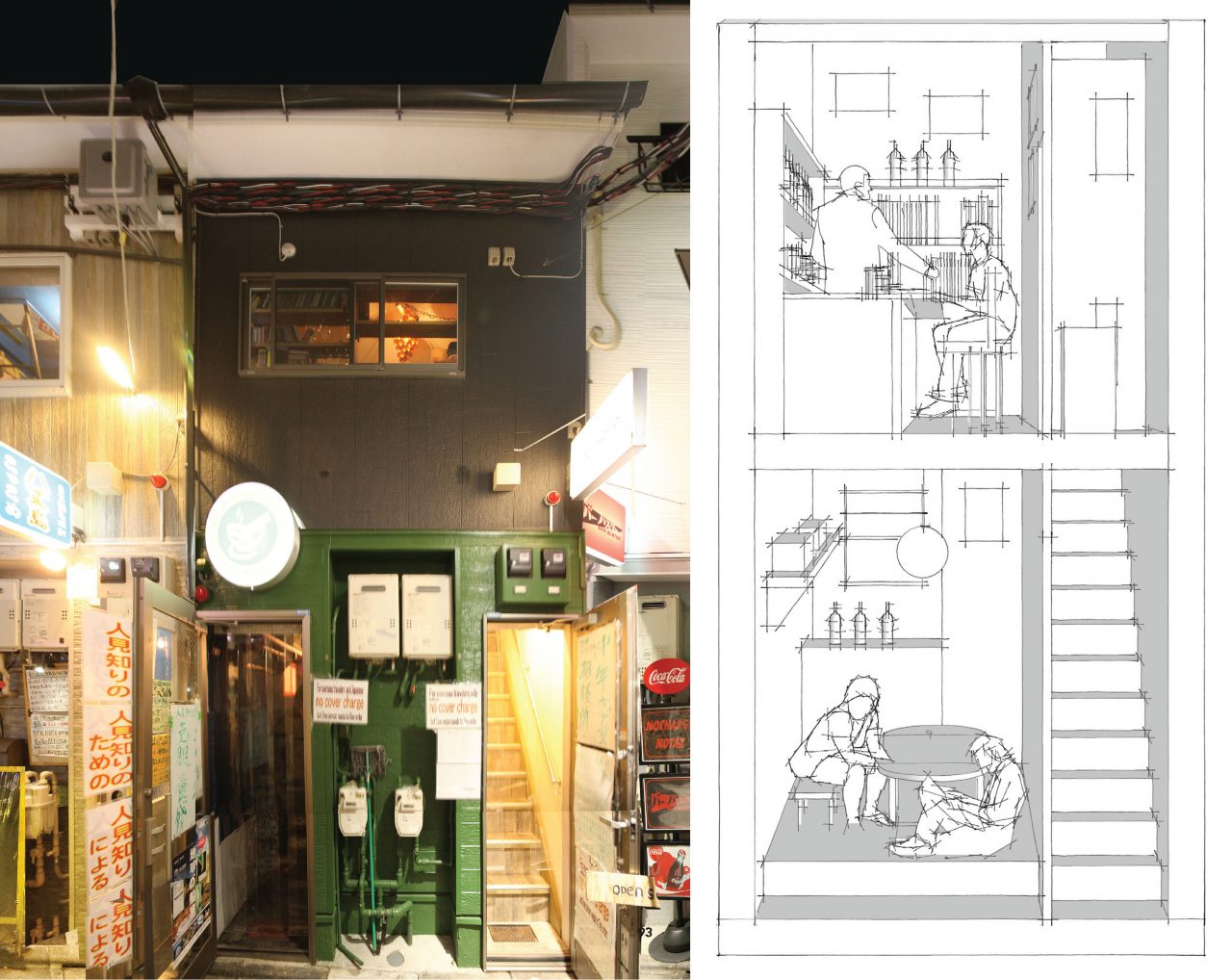

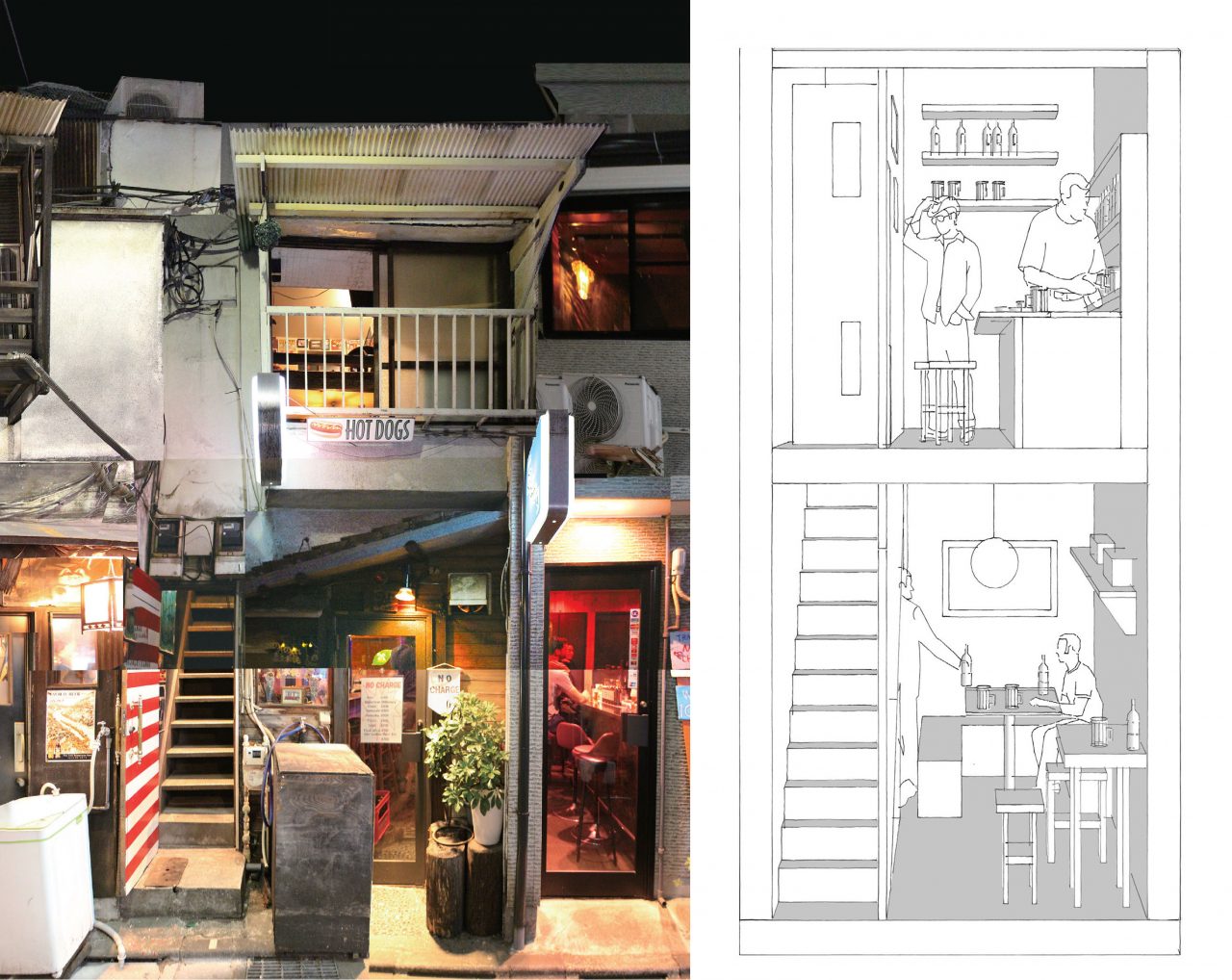

Every Building Storefronts documents four Streets of Golden Gai through drawings, photographs, sounds, and scents.

Four Streets of Golden Gai were documented here. Each side of a different streets was displayed in the same book format placed in a wood table. For the presentation of this work, the photo collages were printed in a scale which you could walk througn the buildings and be able to notice all the small elements such as plants, signs at the door, decorations, lights and so on. Therefore, a 1:20 scale was chosen for the elevation, which resulted in a 2.4 meter-long printed sheet of paper. Both sides of the street was displayed on opposite tables facing each other, creating a pathway in the middle of the exhibition for people to walk through, as if they were in one of the narrow alleys themselves. Then, after the spectator walks along the shops and when in the end of the street, they need to turn the long page of the book to visit another street.

At some points, the user can experience some sounds of Golden Gai district such as people talking both in English and in Japanese, fire alarms, footsteps, the voices of bartenders inviting people to come in and so on. We recorded these sounds in the field and played them on speakers placed in holes at the table along with the books. Also, we collected several smells of the place which jointly help us to evoke the memory of the place through our senses. Some samples of smells are whiskey, shochu, yakitori, perfume, ramen. The substances were put into glass test tubes, which were covered by a black tape, making it impossible to see what is inside the tube: visitors had to guess what the smell is. All these sensations helped to construct the image of the Golden Gal.

Instructors

Ana Miljački

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto

Teaching Assistants

Hyunsoo Kim

Taymour Senbel

Noemi Gómez Lobo

Gallery Guests

Kayoko Ota

Yasutaka Yoshimura

David Stewart

Taishimi Shiozaki

Fuminori Nousaku